The major suit differs from the minor suits not only in the richness and complexity of its card illustrations, but also in its less orderly and more chaotic structure. The four minor suits follow a fully predictable pattern. After the 4 of cups comes the 5 of cups, and just as there is a knight of swords, there is a knight of coins. In contrast, the cards in the major suit display a complex and unpredictable sequence. To demonstrate this point, let us consider a situation where someone sees all the cards from the beginning of the major suit up to a certain card. From this information, he would still have no way of guessing the title or the subject of the card which follows.

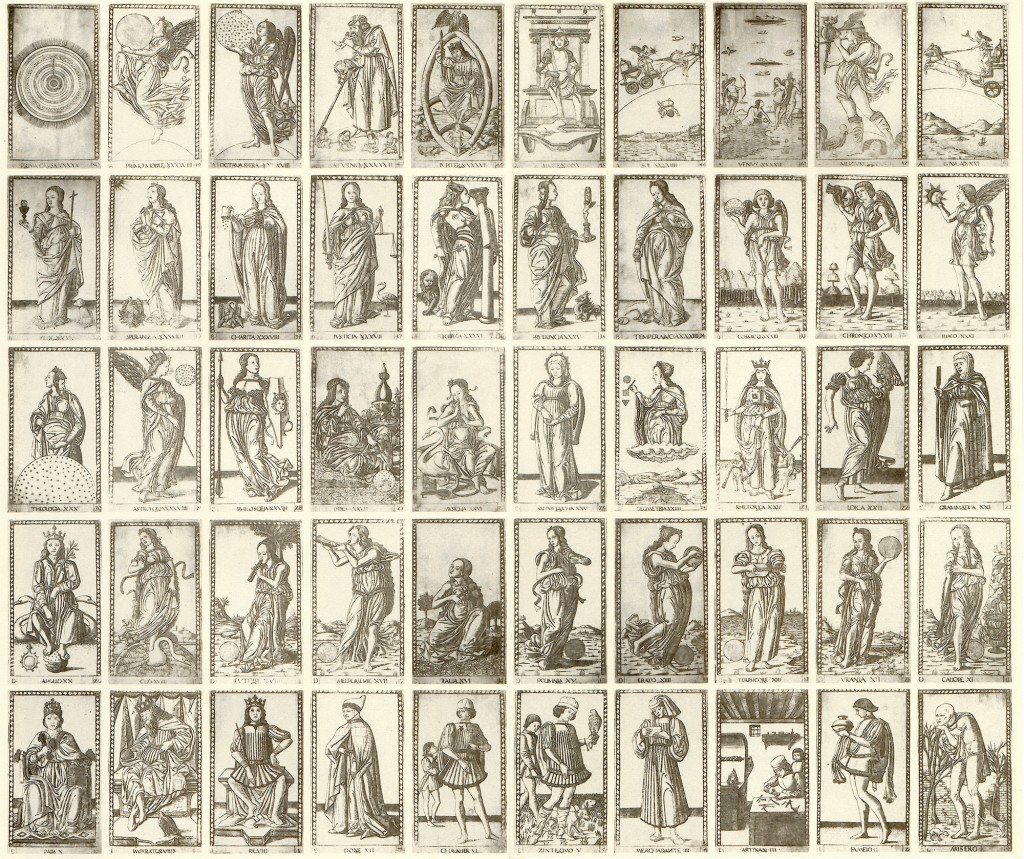

This characteristic sets the major suit apart from other systems of symbolic illustrations which were common during the Renaissance. An interesting example is a collection of card-like prints from the later 15th century. They are known as Tarocchi del Mantegna (“The Tarot of Mantegna”), although they are not really Tarot cards and the attribution to the famous painter Mantegna is unfounded.

The Mantegna prints are divided into five suits of ten images each, with symbolic subjects taken from the conceptual world of the Renaissance. The five suits represent themes like professions and social positions, liberal arts and sciences, the nine muses, moral virtues and celestial objects. Some of the subjects are similar to Tarot cards. For example, there is an Emperor, a Pope, and images representing Force, Justice, the Sun and the Moon.

Still, the Mantegna prints are very different from the Tarot. First of all, it is not even clear that they were meant to be used as a deck of cards. In the surviving originals the images are printed on thin paper and bound together as a book, perhaps for educational purposes. This gives them a well-defined and single standard ordering. In contrast, Tarot cards can be arranged and read in any order. This means that there is an element of chaos which is inherent to the Tarot cards already by the fact that they exist as a set of separate images that can be freely arranged.

The more orderly character of the Mantegna prints is further expressed in the regular structure of the five suits, none of which are exceptional in size or structure. All the illustrations are consecutively numbered, and each one of them has a title written at the bottom. Moreover, when sets of symbols are used they are presented in their completeness. For example, all the nine muses appear consecutively without any one missing, and the same is true of the seven traditional planets, the four cardinal virtues and so on.

In contrast, the Tarot major suit presents a complex interplay between order and chaos. Time and again orderly patterns appear, and time and again they are broken. Each rule seems to have its exceptions, and the exceptions again differ from each other.

Most cards in the major suit carry titles and ordinal numbers. But the two cards that we have already discussed as representing time in the previous chapter, The Fool and Card 13, are exceptional. Card 13 has no name, and The Fool has no number. In addition, there is an empty band on top of The Fool card where the number should be, but there is no similar band for the missing name in Card 13. This means that each one of them is exceptional in its own way.

Trying to go over the major suit cards by sequential numbers, as a way of establishing a standard ordering, proves to be quite confusing. Already The Fool is problematic because without a number we can’t know for sure where it should be. Putting it aside and looking at the sequence of the other cards, we quickly find that it is very difficult, if not impossible, to find any clear logic.

Just after the beginning of the suit there are four cards with figures of authority and government, in an order which is surprising by itself: The Popess, The Empress, The Emperor, and The Pope. But both before and after them there is something completely different. The Magician which precedes these respectable figures looks like a dubious street person. And after The Pope with its Christian symbols there is something even stranger: The Lover with a pagan Cupid and three human figures touching each other. It’s not clear exactly what we see here, and why it appears right after the four representative figures of the established social order.

More patterns appear further along the line just to break down once again. Three major cards present, at equal intervals, three of the four cardinal virtues in Christian tradition: Justice (number 8), Force (11) and Temperance (14). But the fourth virtue, Prudence, is missing. The Temperance card presents another exception. It is the only card in the major suit whose French name is written without the definite article, “Temperance” and not “La Temperance.”

Further along the suit there are three cards with astronomical and alchemy-inspired symbols: The Star, The Moon, and The Sun. Yet before them we find The Tower, with a different symbolic language whose origin is unclear. And after these cards comes The Judgment card which is again linked to Christian symbolism.

Many Tarot books over the last two centuries have tried to find a uniform and logical order in the major suit. Some of their authors have based their attempts on the ordering of the cards, for example by dividing the suit without The Fool into three sets of seven cards, or into seven sets of three cards. More complex patterns were also tried. None of them have proved convincing enough to gain general acceptance.

Other authors have tried to find order in the cards by imposing a system of symbols taken from other sources. For example, many have tried to establish a correspondence between the major suit cards and the astrological symbols of planets and zodiac signs. But each have notably done so in a different way. The Golden Dawn order leaders tried to integrate the cards into their huge table of world-wide correspondences. But again, a disagreement soon appeared as to how exactly to do it. Apparently, in each of these schemes some cards naturally find their place. But then there are others which do not fit so easily, and finally there are some that really have to be forced into their corresponding slots.

Some of the correspondences created over the years are interesting, and may enrich our understanding of the cards. One such example is the correspondence between the cards and Hebrew letters outlined later. But perhaps we should not attach too much importance to any orderly table or any scheme for the definite arrangement of the cards. The breaking of patterns in the major suit could itself carry an important message for us.

Scientists today speak of the phenomena of life as emerging “on the edge of chaos,” a sort of intermediate region between chaos and order. The perfect order is expressed by a solid crystal where everything is well-ordered and fixed. It has no potential for movement, and thus no place for life. The total chaos is expressed by smoke which has no stable shape. Here too there can be no life, because every structure would quickly dissipate. Biological and social life processes take place somewhere in between the crystal and the smoke. They are characterized by a certain degree of order and stability, but also by creative unpredictability and an occasional collapse of ordered structures.

The cards in the major suit, which express and reflect the infinite complexity of life, can also be thought of as a system on the edge of chaos. They show some degree of order and structure, but also chaotic irregularities and pattern-breaking. Therefore it might be pointless to look for an ultimate structure behind them. The only pattern in the cards is the cards themselves.

this text was reprinted as: Order and Chaos in the Major Suit – Tarosophist International, Vol 1 issue 20, August 2013